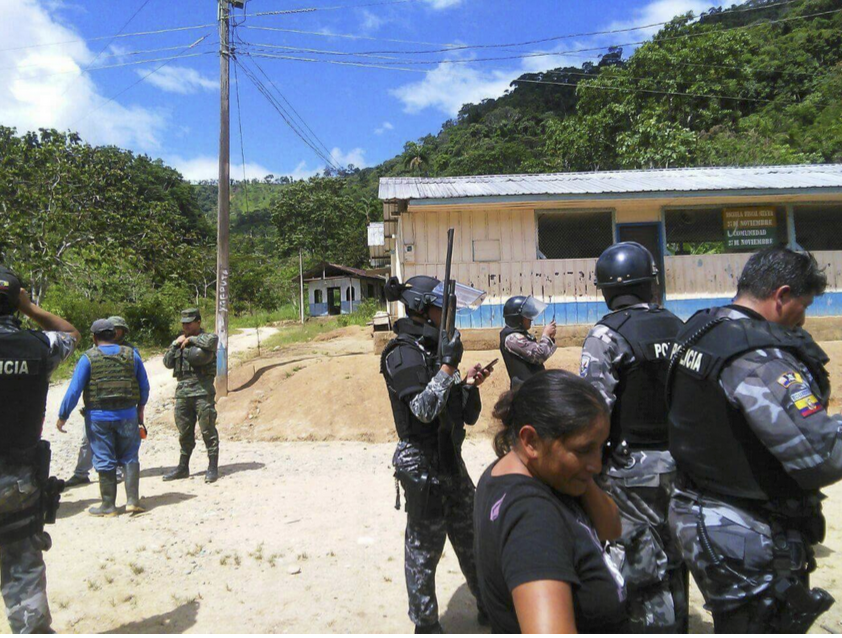

Before dawn on the Dec. 21, 2016, dozens of police raided the headquarters of the Shuar Federation (FISCH) in the Ecuadorian Amazon and arbitrarily detained its president, Agustin Wachapá. The indigenous leader was thrown to the ground and repeatedly stamped on and ridiculed beneath the boots of police in front of his wife. The police then […]

-

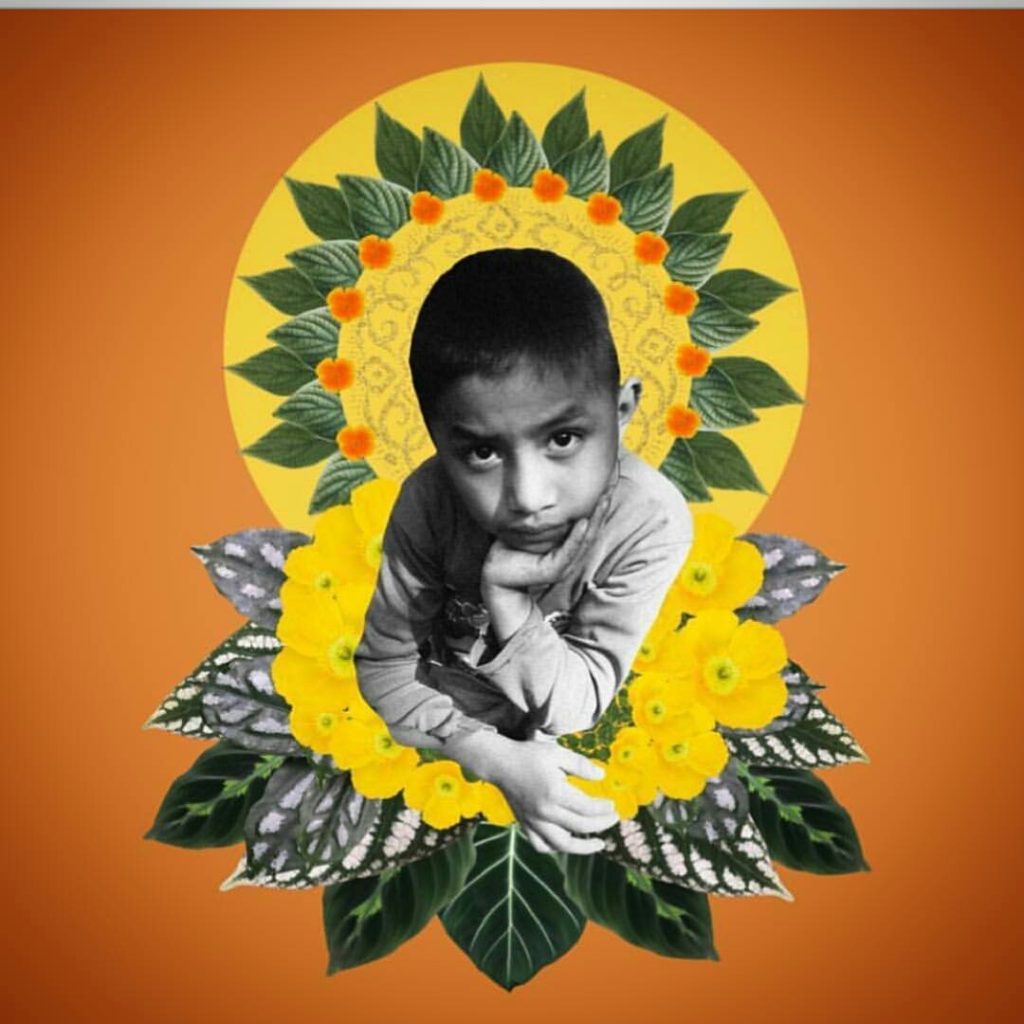

The American Borderlands and the Rights of the Child

// jaco // Esperanza Project Tags: Detebtion Camps, International Law, Tornillo, U.S.-Mexico Border No Responses

Published on Esperanza Project: On Christmas Eve, 2018, in a remote corner of the Texan desert, Esperanza Project editor Tracy Barnett interviewed activists organizing a creative resistance against the detainment of thousands of youths at the now defunct Tornillo Child Detention Center. It was deep in winter and the wind bit at the chain-link fence […]

-

War, Petroleum, and Profit

// jaco // IC Magazine Tags: Amazon Watch, Mining, Petroleum, U'wa No Responses

This is the final installment of “The Guardians of Mother Earth,” an exclusive four-part series examining the Indigenous U’wa struggle for peace in Colombia. The vast wetland savanna called Los Llanos stretches thousands of miles into Venezuela but it begins on the U’wa’s traditional territory at the base of the foothills below the cloud forests […]

-

The legacy of Berito Cobaria

// jaco // IC Magazine No Responses

Published on IC Magazine: This is the third installment of “The Guardians of Mother Earth,” an exclusive four-part series examining the Indigenous U’wa struggle for peace in Colombia. In the cloud forests on the eastern cordillera of the Colombian Andes there is no internet, and phone reception is limited to a few lookouts on the […]

-

They say the land is dead, but it lives yet

// jaco // IC Magazine Tags: Colombia, Rivers, Venezuela, Water Protectors No Responses

Published on IC Magazine: This is the second installment of “The Guardians of Mother Earth,” an exclusive four-part series examining the Indigenous U’wa struggle for peace in Colombia. Nestled below the snow-capped mountains on the eastern cordillera of the Colombian Andes is the town of Güicán, known internationally to hikers as the gateway to Colombia’s […]

-

The Guardians of Mother Earth

// jaco // IC Magazine Tags: Colombia, FARC, U'wa, U'waa No Responses

Published on IC Magazine: This is the first installment of “The Guardians of Mother Earth,” an exclusive four-part series examining the Indigenous U’wa struggle for peace in Colombia. On September 23, 2015, in the Palace of Conventions in Havana, Cuba, his excellency Juan Manuel Santos, the President of the Republic of Colombia, and Commander Timoleon […]

-

Pedro Canché: the Maya journalist running circles around Mexican media

// jaco // IC Magazine No Responses

Published on IC Magazine: Five days ago, the tropical island of Holbox, off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, caught fire. Reports of smoke billowing over the uninhabited southern tip of the island were first shared over social media on Saturday afternoon, Sept. 17, while Pedro Canché, known across the Yucatan as “the Maya journalist”, prepared to interview […]

-

Ecuador’s Indigenous Uprising

// jaco // IC Magazine Tags: Ecuador No Responses

Published on IC Magazine: As Andean winds carry mild amounts of ash from the mouth of the Cotopaxi volcano toward the Ecuadorian capital city of Quito, 500 kilometers away, a State of Emergency is in full effect. The government declared the State of Emergency last week purportedly in response to Cotopaxi’s eruption. However, many indigenous […]